- Home

- Cary Holladay

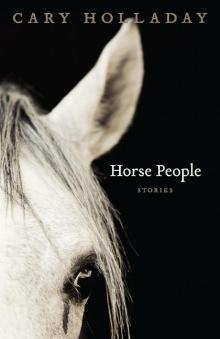

Horse People

Horse People Read online

Horse People

YELLOW SHOE FICTION

Michael Griffith, Series Editor

Horse People

STORIES

Cary Holladay

LOUISIANA STATE UNIVERSITY PRESS

BATON ROUGE

Published by Louisiana State University Press

Copyright © 2013 by Louisiana State University Press

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

LSU Press Paperback Original

First printing

DESIGNER: Michelle A. Neustrom

TYPEFACES: Whitman, text; Tribute, display

PRINTER AND BINDER: McNaughton & Gunn, Inc.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Holladay, Cary C., 1958–

Horse people : stories / Cary Holladay.

p. cm.— (Yellow shoe fiction)

“LSU Press Paperback Original”—T.p. verso.

ISBN 978-0-8071-5094-8 (pbk. : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-0-8071-5095-5 (pdf) — ISBN 978-0-8071-5096-2 (epub) — ISBN 978-0-8071-5097-9 (mobi) 1. Virginia—Fiction. I. Title.

PS3558.O347777H67 2013

813’.54—dc23

2012038888

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, organizations, places, circumstances, and events are the product of the author’s imagination, or else they are used fictitiously. Any depictions of historical figures are invented and are not intended to alter the fictitious nature of the work. In all other respects, any resemblance to actual occurrences, locales, or individuals, living or dead, is coincidental.

Portions of this work have been previously published in slightly different form: “The Bridge,” Hudson Review 56, no. 4 (Winter 2004); “Seven Sons,” Hudson Review 64, no. 3 (Autumn 2011); “Monstrosities,” Georgia Review 59, no. 4 (Winter 2005); “Nelle on the Grass,” Idaho Review 5 (2003); “The Colored Horse Show” as “Horseman, Pass By!,” Sewanee Review 119, no. 1 (Winter 2011); “Two Worlds,” Southern Review 46, no. 3 (Summer 2010); “Hollyhocks,” Five Points 10, nos. 1 & 2 (2006), and New Stories from the South: The Year’s Best 2007; “Horse People,” Ecotone 4, nos. 1 & 2 (2008), and New Stories from the South: The Year’s Best 2009.

The paper in this book meets the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Committee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources.

For John

First to hear my news, be it merry or sorry

CONTENTS

The year in parentheses indicates the time

of the major action in each story.

RAPIDAN, VIRGINIA

The Bridge (1861)

A Summer Place (1889)

Seven Sons (1910)

Monstrosities (1920)

Nelle on the Grass (1932)

The Colored Horse Show (1945)

Two Worlds (1950)

Hollyhocks (1953)

Horse People (1927)

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Horse People

The Bridge

Bonnie Hazlitt can’t remember how it ended, her stint as bridge guard. Like the others, she was hired by Henry Fenton, who was directed by the Orange County Court to employ “four to six discreet persons” to defend the span over the Rapidan River. Strolling along it, Bonnie gazed down into the water, oh, watching and listening for the Yankee army, for spies and traitors, reading the sky for clues, believing the hawks and buzzards would warn her of enemies’ approach. There was plenty of traffic, neighbors and tradesmen and rebel soldiers. Bonnie had the morning hours, starting at sunrise. She had a baby at home; her mother took care of him. Bonnie was not respectable, but Henry Fenton saw beyond that, and she was grateful to him.

It made sense that Henry Fenton was in charge. His flour mill sat on the riverbank.

Strategic—that’s a word Bonnie learned from Henry Fenton. The village of Rapidan had a strategic location. Cross the Rapidan River, and you’re in Culpeper County. Every time Bonnie makes that few minutes’ trip, it feels important. A change, a miracle almost, to step from one county to another.

Even then, back in 1861, Bonnie must have known she wasn’t accomplishing a damn thing. And she must have got the bighead. That was what her mother said, her mother who believed it was nonsense for a girl to guard the bridge. “You’ll be gettin’ the bighead,” her mother said, and they would laugh. Was it all in vain, those hours of scanning the bridge, the water below, the road to and fro? Maybe she did keep the Yankees away, her vigilance forestalling the marauders who would have pillaged and killed, swept down on Rapidan and routed them all from their homes, farmers and housewives, children and old folks, coloreds and whites, dogs and cattle.

Finally, of course, the Yankees came anyway. Bonnie’s bridge stayed safe. The Orange & Alexandria Railroad bridge, a half mile downstream, was the one they wanted. Three times it burned, never mind there were soldiers guarding it: in July 1862, by General Pope’s Federals, before Cedar Mountain; in May 1864, by Confederates, after the Wilderness; and in September 1864, by New York cavalrymen. That was a bad raid. They tore up telegraph equipment and burned the mill and the depot. Luckily, that time, the trestlework timbers of the railroad bridge were green and were only singed; in two weeks, it was fixed, and trains were crossing again.

Bonnie hid in her house every time.

Years later, in her fifties, her sixties, Bonnie just doesn’t remember how it ended. “Musta been knocked on the head,” she tells her canaries, “the bighead,” twittering back at them, the glosters and fancies, agates and isabels, their feathers silken in her hands. Buyers come from Washington, Richmond, Wheeling. She has a wonderful memory. A knock on the head is the only thing that would interfere with it. She recalls which ones customers purchased years ago. Keeps up with her birds, since her children are gone away—the two sons, that is; daughter stayed in Rapidan. “Boys’re still alive, far as I know,” she observes as she cleans cages. “Bonnie’s Beauties,” says the wooden sign on her house, the same little house she grew up in. A tramp carved the canary-shaped sign for her and painted it yellow. “Purty thing,” he said of the canary she supplied as a model. By then the war was long over and her mother was dead.

As a bridge guard, she had a gun loaned by Henry Fenton, but she never used it. Her eyes and ears were her best defense, and her strong legs could sprint a warning, miles if need be. Henry Fenton had a telegraph in his mill office. He knew before anybody about the moving armies. What you had to watch for were strays, outsiders. Horseman, swimmer, fisherman. You would not know him, when you saw him.

She did not hesitate to question strangers. Three times, heart in her throat, hand on the gun, she took someone to Henry Fenton’s office. Each time, Henry greeted the man by name. “Don’t she look sheepish,” one man chuckled, but Henry praised her. How much was she paid? She can’t remember that either, all these years later, when her thoughts are all for her canaries. A few dollars, she guesses, paid by Henry Fenton in his mill office. She put the money down her dress and didn’t care who saw.

One day she saw a white squirrel. It made her happy, that flash of exotic fur high in a tree along the river, something natural that yet did not belong. She was glad for the war, for it meant there were fewer men and boys to hunt the squirrel, to kill it. “Mens is so cruel,” said the Negro midwife who delivered Bonnie’s baby. The woman told tales of the colored world, of a wife killed by her husband and found with eyes wide open and hands in front of her face as if to push her murderer away. The teller demonstrated, lying on the ground with hands up and eyes wide for the benefit of Bonnie and her mother. Everybody knew it was poison, the woman said, because of the staring eyes, and a white line like salt on her lips.

Flash, scurry.

The white squirrel showed itself only to Bonnie. It is her most vivid memory of the war, and maybe of her life, what she would see if she died. Not her long-ago first baby that went to Mexico; not Henry Fenton whom she loved sort of, though she’d have died if he’d guessed it; not those morning hours when she was a vital shield protecting Rapidan; not even her canaries so soft in her hands. But a white squirrel, glimpsed in a stand of box elder by the Rapidan River—her best memory. She likes to think the squirrel is still there. The same one.

Henry Fenton’s own wife, Mary Jane, is the most discreet person he knows. He would deploy her to the bridge, and she would gladly go, but since the birth and death of their daughter, Lizzie, she has been sick. Mary Jane suggested who the guards might be, after careful thought, speaking the names clearly from her bed: Bonnie Hazlitt, the Pratt twins—old men—and a boy named Burrell Taliaferro—“Tolliver,” people say it—who has only one eye and is too young to fight.

Because of Mary Jane’s being sick, Henry need not go to war.

In the afternoons, while she tries to sleep, she imagines the pattern that leaves and pine needles would make on tent canvas, with sunlight above them. As a young girl, she toured the Blue Ridge with her cousins Ginny and Dan, an uncle, and an aunt; the aunt was her father’s sister. Mary Jane’s sister Beth didn’t go; Beth was married by then. Beautiful, what Mary Jane saw from the knolls and in the woods. They slept at inns, some none too clean. She begged the others to camp, to sleep in the woods. She longed to look up through a roof of canvas and see fallen pine needles on the thin cloth of a tent, making shade, a kaleidoscope of shadows. Back then, she was strong enough to climb the Peaks of Otter. Now her middle’s been blasted out of her, feels like.

“Tell me everything,” she says to the bridge guards. In turn, they visit her room and sit in her slipper chair. “Tell me who you saw.”

That’s what her mother used to say, every time Mary Jane went out. It drove her crazy, as a young girl. “Who did you see?” her mother asked. “Who did I see,” Mary Jane repeated furiously, for there were so few neighbors. Mary Jane and her sister Beth bewailed their loneliness. Beth married young and moved to Richmond. Their mother expected the world would come to their Spotsylvania County farm, but Mary Jane in bitter triumph knew that it would not. Her parents were Scots living in Ireland when they fled for their lives, changing their name from Livingston to Boggs. Such an ugly name, Mary Jane thinks, as two of the bridge guards, the old Pratt twins, begin their recitation.

“We stopped a horse and wagon,” they say, “and searched it. What was in the wagon was all lumpy, under old rugs.”

“Let me guess,” says Mary Jane. But everything is lumpy under old rugs. Her fever is coming back, and that sensation of her body slipping out of itself, silencing her.

“It was ornaments,” a Pratt says, fumbling for the word. “Pretty things. Lanterns, stars, all different colors. For a party, the man said.”

“How old are you?” asks Mary Jane. Sometimes, pain jolts her mid-sentence, taking her to a place she thinks of as hold still, bear it.

“We are seventy,” responds one man, as if the age is permanent.

“What is it like?” she asks, and they think she means not their twinship but their duty.

“It’s all right,” they say together.

“I can’t tell the two of you apart,” she says. “Can anyone?”

“Yes, ma’am,” they say. “We can tell us apart.”

“Now listen,” she says. “The way I see it, there won’t be just one battle, been and gone. Our soldiers and the Yankees will be all through here, the whole time this war lasts. This will be contested territory.” The Pratts couldn’t scare crows from a cornfield. “We can’t let them have it. To guard the bridge, you have to love it. Do you?”

Miz Fenton is scarier than the Federals. “Yes, ma’am,” the Pratts chorus. They’ve never said the word love in their lives, except about apple butter, the way their mother made it.

The boy, Burrell, has the dead-of-night watch. He loves it. Animals come by then, trotting, lolloping, slithering, flying, padding, powered by their invisible hearts, their eyes bright as coins. He had never known that they too use the bridge, not just the wild and tame dogs that cross it during the day, but possums and deer, foxes and bobcats, as if to say, Why not, it’s here. He thinks he’s dreaming when herd animals appear: goats and sheep, one or two as if ark-bound. They have business to tend to. He could reach out and pet their flanks, their hides. He tries, and they swerve out of reach. Porcupine, bear, turkey, squirrel, and pig. Their nighttime travels have a dapper purpose and camaraderie. Snakes move fast at night, and toads jump high as Burrell’s shoulder. Tortoises, he swears, nearly gallop. They have no fear of him, this boy crouched at one end of the bridge, proud of missing his sleep.

When he recites the list of creatures, he grows insistent, turning his good eye toward Mary Jane Fenton, cocking his head.

“I believe you,” says Mary Jane. “I know they are there. I’ve heard them.”

Her house overlooks the mill and the river. She herself would be the best guard of all.

“It’s not like people think it is,” he says, meaning the animal world, the night world. Burrell unwraps his sketchbook. He has drawn them, the creatures. Among their figures float faces and forms of humans, caught in his lantern light as he hailed and detained them, then let them pass. Mary Jane barely glances at those.

“Here’s an owl riding the back of a mule,” she says, delighted.

“They came by ’bout three o’clock,” says Burrell.

It’s early in the morning, and he’s sleepy, his shift having ended with sunrise, when Bonnie Hazlitt swung down the road wearing a yellow apron over her dress. He longs to be dashing and witty in her eyes, but believes she dislikes him.

“Go home,” Mary Jane tells Burrell, “and rest.”

“How can you hear ’em? The animals.”

“I often sleep with the windows open. Sounds carry, at night, and over water.” She blushes, for this is Henry’s room, too.

Burrell folds his sketchbook and lopes away.

All over the South there are bridges, and some with guards. Are they all like this, busy at night with animals in transit? Mary Jane has seen the army, southern soldiers. When men are coming, Henry often has word. From her window she watches the long assemblage with its music, its shouts, drumbeats, a cavalcade and parade. Men find their way to her door, and her cook feeds them. Commanders stop at the mill, and Henry greets them. The bridge holds them all, men, horses, wagons. For miles after they pass, she can glimpse them on the rising road as the column winds through farms and up into the hills.

“Throw him back like an ugly fish,” says Henry, his eyes twinkling, when the guards ask what they should do if they apprehend a Yankee. He expects, before the war ends, that they may all have to fight, at least the old men and the one-eyed boy. That girl, Bonnie Hazlitt, could nurse her baby and do battle at the same time, don’t put it past her.

Don’t ever say good-bye on a bridge. You’ll never see the other person again, Henry’s grandmother used to say. From the top floor of his mill, the railroad bridge and the river bridge both look as far away as the Grand Canyon must be. He knows exactly how far it is to points in all directions. North to Culpeper, 13 miles. Northeast to the Manassas battlefield, 52. Southeast to Richmond or northeast to Washington, D.C., 82, Rapidan being equidistant. East to Spotsylvania Courthouse, 33. Southwest to the Peaks of Otter, 135.

Henry’s mind wanders; geography and history are great loves. He could spend all day with maps. Rapidan, he knows, was called Waugh’s Ford when it was hewn out of forest and floodplain some hundred years ago. The Waugh clan, farmers and tradesmen, still populate the area. The swift river was named the Rapid Anne for the queen of England. Long time a mill’s been here, flourishing, though Henry’s is bigger and better than its predecessors. When the railroad came, the village was renamed Rapid Ann Station.

All his

life, Henry has heard the train. Its song is his anthem.

He is thirty-three years old. Landowner, horse breeder, yet on this warm evening in his tall mill—the largest in the region, with six sets of grindstones—he feels helpless, powerless. The daughter he had with Mary Jane lived two years, during which she and Mary Jane were usually sick.

His wife will die too. Then he’ll go to war. She’ll die and I’ll fight. The realizations slice through him while he bargains with two farmers. He speaks and smiles, but he is wood. Can’t they see it? He and the farmers have reached some agreement. They shake hands there with the view of river and mountains and trees. Oh, the old mill’s got mice in the walls, mice clever and swift on tiny feet, mice running for their lives up and down the steep winding stairs, riding the lift. In Henry’s dreams, they work the machinery. Mice know Henry could not for the life of him say what he and the farmers have agreed on. The farmers are telling jokes, pleased with the deal. When he says, I don’t remember a word I’ve just said to you, the men’s laughter is a roar. That Henry Fenton, they’ll say.

Most of his horses are gone to war. The army took them, even his favorite, Bessy Bedlam, the best steeplechaser in five counties. A painting of Bessy Bedlam hangs on the wall of the room he shares with his wife. Go get ’em, Bessy, he says when he looks at the picture. The painter made Bessy’s coat too brown. She is bay.

He is alone in his high office with a chunk of petrified wood on his desk as a paperweight on a stack of orders and bills. The farmers are gone and it is evening, time for supper. A train sounds, lonely and loud, and when it passes into the distance, he can hear his own heartbeat. His wife is sick and their daughter dead. His workers are silent, if they are here at all. Did he send them home already? The mice are silent. Down on the river bridge the two old Pratts, bowlegged as wishbones, face away from each other, one picking his nose, the other scratching his stomach. Never say good-bye, Henry’s grandmother said, on a bridge. His wife is a Scot. Building cairns is in her blood. The sun moves toward setting. The war surprised him, threw him. Thrown, as if from a horse. He can’t get up from his chair. The mice must be striking all kinds of crazy positions in the walls, on the stairs, in the piles of grain, mocking him. It would have taken him forever to choose the bridge guards. The war would have ended before he decided. So Mary Jane, cairn builder, did it. She’ll be having her supper on a tray in her room, watching the sundown birds.

Horse People

Horse People